The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) is a natural climate pattern in the tropical Indian Ocean that changes sea-surface temperatures (SSTs) between the western and eastern parts of the basin. These changes strongly influence rainfall, droughts and marine ecosystems across East Africa, South and Southeast Asia, Indonesia and Australia. Understanding the Indian Ocean Dipole helps communities, farmers and policy makers prepare for floods, droughts, fisheries shifts and extreme weather. (Definitions and overview from the Bureau of Meteorology and NOAA).

Indian Ocean Dipole

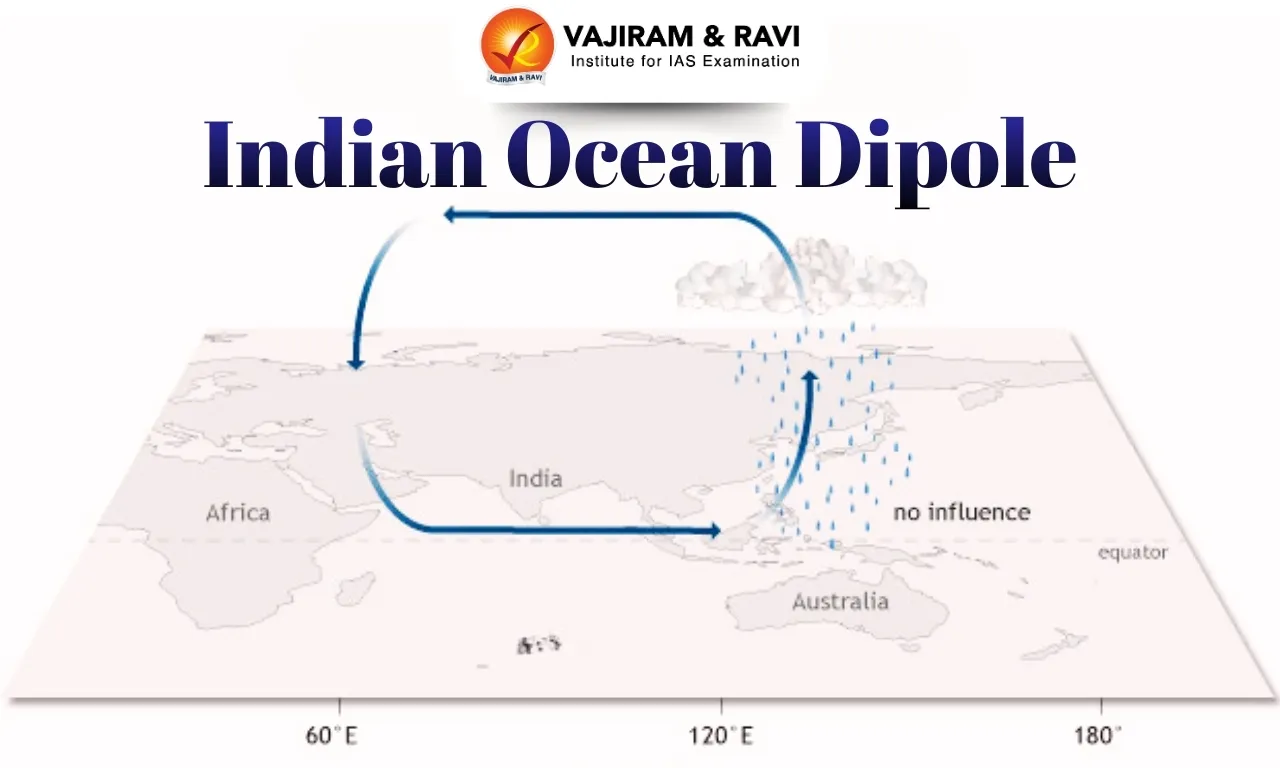

The Indian Ocean Dipole is an oscillation in sea-surface temperature between the western Indian Ocean (near East Africa) and the eastern Indian Ocean (near Indonesia). When the western Indian Ocean is warmer than normal and the east is cooler, the IOD is in a positive phase; when the opposite occurs it is in a negative phase. A neutral phase is when there is little difference. The IOD strongly affects how moisture, winds, and clouds develop over the Indian Ocean and surrounding land regions, influencing weather, rainfall, and climate patterns in East Africa, India, Indonesia and Australia. IOD events typically develop during boreal summer and peak in September-November.

Indian Nino

The term "Indian Nino" often refers to the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), which is a climate phenomenon similar in concept to El Niño/ La Niña, but it happens in the Indian Ocean, not the Pacific. The Indian Ocean Dipole is defined by the difference in sea-surface temperature (SST) anomalies between two key regions: the western tropical Indian Ocean (near East Africa) and the eastern tropical Indian Ocean (near Indonesia).

Indian Ocean Dipole Causes

The Indian Ocean Dipole arises from coupled ocean-atmosphere interactions: differences in sea temperatures change winds and rainfall, which feed back on ocean temperatures. Remote influences such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) modulate the IOD, but the IOD can also arise from local atmospheric variability. Subsurface ocean conditions (thermocline depth) and seasonal cycles shape how an event grows and decays.

- Air-sea coupling: SST anomalies alter winds; winds change ocean upwelling and SSTs, this feedback drives the IOD.

- ENSO link: El Niño often precedes or enhances a positive IOD, but IOD can occur without ENSO. Predictability depends partly on ENSO.

- Thermocline changes: shoaling (shallower) thermocline near eastern Indian Ocean supports cooling/upwelling during positive IOD.

- Seasonality matters: most events form in June-August and peak in Sep-Nov (boreal autumn).

Indian Ocean Dipole Phases

The Indian Ocean Dipole Phases produce broadly opposite climate outcomes across the rim of the Indian Ocean.

Positive IOD

West warmer → stronger convection/ rainfall over East Africa; East cooler (off Sumatra/ Java) → suppressed rainfall → drought in Indonesia and parts of Australia. This pattern contributed to the severe 2019 East African floods and Indonesian drought and fires.

Negative IOD

East warmer → enhanced rainfall over Indonesia and northern Australia; West cooler → reduced rainfall in East Africa. Negative IODs can increase Australian rainfall and flood risk.

Neutral

Little or no contrast; impacts close to climatology.

Indian Ocean Dipole Events

Notable Indian Ocean Dipole events provide clear examples of its societal impacts.

- 2019 positive IOD: One of the strongest on record; linked to severe drought in Indonesia, major fires and anomalous East African rainfall leading to floods. Studies show it strongly influenced the 2019 Australian bushfire season and regional ecological disruption.

- 1997-98 positive IOD: Earlier strong positive event with notable regional impacts on rainfall patterns.

- 2021-2022 multi-year negative IOD: Extended negative conditions in 2021-22 were unprecedented in duration and co-occurred with multi-year La Niña, affecting marine productivity and regional precipitation. Recent studies document this long event.

- Extreme events can cause abrupt ecosystem responses, for example, chlorophyll and fisheries changes detected after strong IODs.

Indian Ocean Dipole and the South Asian Monsoon

The Indian Ocean Dipole influences the Indian summer monsoon and regional rainfall patterns, sometimes reinforcing or counteracting ENSO effects.

- Positive IOD tends to enhance monsoon rainfall over India or offset El Niño-related weakening, depending on timing and strength. Studies show IOD can modulate monsoon variability.

- Negative IOD can be associated with below-normal monsoon rainfall in some regions, but the relationship is complex and interacts with ENSO and local drivers.

- The combined state of ENSO and IOD matters: an El Niño with positive IOD may produce different monsoon outcomes than El Niño alone.

Indian Ocean Dipole Impacts

The Indian Ocean Dipole affects food security, health, ecosystems and economies across affected countries.

- Agriculture: Droughts or floods tied to IOD change cropping outcomes, reduced yields, failed sowing or season shifts in India, Indonesia, East Africa and Australia.

- Fisheries & marine life: SST and upwelling shifts change plankton, fish distribution and productivity, with implications for coastal communities. Satellite analyses show increased chlorophyll in eastern Indian Ocean during some events.

- Health & disasters: Floods boost vector-borne disease risk; droughts increase malnutrition and water stress. Extreme IODs have been linked to severe fires and public health crises.

- Economic losses: Infrastructure damage from floods, crop losses, and reduced fisheries income cause significant economic harm and heighten vulnerability for poor communities.

Indian Ocean Dipole Interactions

The Indian Ocean Dipole does not act in isolation, ENSO, the monsoon circulation and regional weather modes interact with it.

- ENSO (El Niño/La Niña) often influences or is influenced by the IOD; El Niño events frequently co-occur with positive IODs, boosting predictability but also complicating attribution

- IOD variability can either amplify or partially offset ENSO impacts on regional rainfall.

- Other drivers (Indian Ocean Basin-wide warming, Madden-Julian Oscillation, local monsoon dynamics) also affect how IOD plays out each year.

Indian Ocean Dipole Monitoring

Scientists use tools and observations to monitor the Indian Ocean Dipole and issue seasonal guidance.

- The Dipole Mode Index (DMI), difference in SST anomalies between western and eastern tropical Indian Ocean boxes, is the standard index to detect IOD. Agencies like Australia’s BOM and NOAA publish DMI and forecasts.

- Seasonal forecasting systems combine ocean observations, satellite data and coupled climate models to predict IOD development months ahead, though skill varies.

- Monitoring networks include Argo floats, satellites (SST, altimetry), and in-situ buoys; these feed models and early warnings used by meteorological services.

Indian Ocean Dipole Climate Change Effect

Climate change can alter the frequency, intensity and impacts of Indian Ocean Dipole events, but uncertainties remain.

- Climate models and assessments (IPCC and recent research) indicate a potential increase in extreme IOD events with warming, although projections vary by model and scenario. This could raise the risk of severe droughts and floods in rim countries.

- Warming alters background SST and atmospheric circulation, which changes the baseline on which IOD anomalies develop, potentially increasing extremes or changing seasonality.

- The IOD-ENSO relationship might shift under climate change, complicating future predictability and regional impacts. Continued research and model improvements are essential.

Indian Ocean Dipole Response

Governments and communities can reduce harm from IOD-related extremes with planning based on forecasts and resilient systems.

- Early warning systems that integrate IOD forecasts with local impact models allow timely actions (crop choices, water storage, health measures).

- Climate-smart agriculture (drought-tolerant crops, flexible planting dates) reduces crop losses when IOD signals predict dry seasons.

- Ecosystem-based approaches, mangrove restoration, sustainable fisheries management, help buffer ecological impacts.

- Regional cooperation among Indian Ocean rim nations improves data sharing, joint forecasting and coordinated disaster response.

What Is El Niño and La Niña?

El Niño and La Niña are the two opposite phases of a climate pattern called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which involves interactions between the tropical Pacific Ocean and the atmosphere.

- El Niño is the warm phase: sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the central and eastern Pacific become unusually warm, trade winds weaken, and the typical upwelling of cool water along the South American coast slows down.

- La Niña is the cold (or “cool”) phase: SSTs in the same region drop below normal, trade winds strengthen, and upwelling of cold water intensifies.

These phases are not just ocean phenomena, they strongly influence atmospheric pressure, winds, and global weather patterns.

- ENSO cycles irregularly; there is no fixed period.

- El Niño often reduces rainfall in some tropical regions (for example, it can suppress the Indian monsoon).

- La Niña tends to enhance precipitation in certain places; but its impacts vary depending on geography and other climate drivers.

Indian Ocean Dipole and La Niña 2025

In 2025, climate observations and forecasts point to a negative Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) and a weak La Niña event co-occurring, which have combined and interacting effects. They influence each other and their combined or separate impacts might be as:

- According to IMD (India Meteorological Department) bulletins, weak La Niña conditions persisted in early 2025 and are expected to transition to ENSO-neutral by mid-2025.

- Current forecasts (as of November 2025) confirm that neutral ENSO conditions are prevailing, but models indicate an increased likelihood of La Niña conditions developing in the coming months.

- Several sources report that by mid-2025, the IOD index had dropped below −0.4°C (the threshold for a negative IOD event), indicating a sustained negative IOD.

- As per The Bureau of Meteorology, The negative IOD event remained active (index value rising to -1.57 °C) as of November first week.

- A negative IOD typically brings more moisture to Indonesia and northern Australia because warmer water in the eastern Indian Ocean boosts convection and rainfall there.

- From a combined perspective, when La Niña and negative IOD occur together, they can reinforce each other: La Niña tends to build moisture in the western Pacific, and negative IOD increases moisture from the Indian Ocean, possibly leading to more sustained or intense rainfall in regions influenced by both.

- However, the overlap also has complexity: scientific studies suggest that the interplay between IOD and ENSO is not always linear. For example, a 2024 study showed that a positive IOD reinforces El Niño teleconnections strongly, but negative IOD with La Niña does not always produce a symmetric atmospheric response.

- Therefore, while forecasts suggest both negative IOD and La Niña may be in play in 2025, the exact climate impacts (on rainfall, monsoons, or regional extremes) will depend on how these phenomena interact, seasonal timings, and other climate modes too (like the Madden-Julian Oscillation).

Indian Ocean Dipole UPSC

The Indian Ocean Dipole is a powerful natural driver of climate variability across a densely populated and economically vital region. Positive and negative IOD events bring contrasting patterns of drought and flood, with wide-ranging effects on agriculture, water, ecosystems and human well-being. Scientific monitoring, seasonal forecasting, and climate-sensitive planning reduce risks, but rising global temperatures may increase the frequency or severity of extreme IOD events. Strengthening observations, improving models, and investing in adaptation are essential to protect vulnerable communities that live along the Indian Ocean rim.

Indian Ocean Dipole FAQs

Q1: What is the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD)?

Ans: The IOD is a climate pattern of sea-surface temperature difference between the western and eastern tropical Indian Ocean that affects rainfall and winds across the region.

Q2: How does a positive Indian Ocean Dipole affect India and nearby countries?

Ans: A positive IOD typically causes wetter conditions in East Africa and drier conditions in Indonesia and parts of Australia; its effect on India’s monsoon can be complex and depends on ENSO and timing.

Q3: Can we predict Indian Ocean Dipole events?

Ans: Yes, seasonal forecast models and monitoring systems provide skillful forecasts months ahead, though predictability varies and depends partly on ENSO.

Q4: Did climate change influence recent extreme Indian Ocean Dipole events?

Ans: Research suggests climate change may increase the likelihood of extreme IOD events, but uncertainties remain; studies point to links between warming and stronger 2019-type events.

Q5: How can societies reduce harm from Indian Ocean Dipole impacts?

Ans: Use IOD-informed early warnings, climate-smart agriculture, water management, coastal conservation, and regional data cooperation to prepare for droughts and floods.