The Home Rule Movement in India marked a crucial milestone in the liberation struggle. It was India’s response to the First World War. From 1916 to 1918, the movement gained momentum throughout the country. Prominent leaders such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Annie Besant, G.S. Khaparde, Sir S. Subramania Iyer, Joseph Baptista, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah came together. They recognised the need for a year-round national alliance.

Their primary objective was to demand self-government or home rule for the entirety of India within the framework of the British Commonwealth. This alliance was to be known as the All India Home Rule League, drawing inspiration from the Irish Home Rule League.

Home Rule Movement Causes

The Home Rule Movement emerged as an assertive political movement. Several factors leading to the formation of the Home Rule Movement were:

- The Government of India Act 1909 failed to meet the aspirations of Indians.

- The split within the Congress Party in 1907 and the imprisonment of Bal Gangadhar Tilak from 1908 to 1914 resulted in a period of relative calm in the national movement.

- Some nationalists believed that popular pressure was necessary to achieve concessions from the government. The release of Tilak and the arrival of Annie Besant sparked a revival of the national movement.

- Indian leaders were divided on whether to support Britain in the war, but Annie Besant famously declared, “England’s need is India’s opportunity. “The burden of wartime hardships, such as high taxation and rising prices, made people more willing to participate in aggressive protest movements.

- Upon his return from exile in Mandalay, Tilak recognised the necessity of rejuvenating the nationalist movement in India and acknowledged the growing significance of the Congress Party in the country’s political landscape.

- Tilak’s primary objective was to rejoin the Congress Party, from which the extremist faction led by him had previously separated.

- In the December 1915 Congress session, largely influenced by Annie Besant’s persuasion, it was decided to readmit the extremists into the party and involve them actively in the national struggle.

- However, both Besant and Tilak were unsuccessful in convincing Congress to support their proposal of establishing Home Rule Leagues.

- Besant managed to secure Congress’s agreement to engage in educative propaganda and establish local-level committees. If these conditions were not fulfilled by September 1916, she would be free to establish a Home Rule League.

Two Home Rule Leagues

Tilak and Besant recognised that the support of a Congress dominated by Moderates and the cooperation of Extremists were crucial for the success of the Home Rule Movement:

- Failing to achieve a Moderate-Extremist agreement at the 1914 Congress session, Tilak and Besant decided to revive political activity independently.

- In early 1915, Annie Besant initiated a campaign demanding self-government for India after the war, similar to white colonies. She used her newspapers, public meetings, and conferences to promote her cause.

- The efforts of Tilak and Besant found some success at the 1915 Congress session. The Extremists were admitted to Congress, although Besant’s proposal for Home Rule Leagues was not approved. The Congress committed to an educative propaganda program and the revitalisation of local-level committees.

- Besant set a condition that if the Congress did not fulfil its commitments, she would establish her league. Due to Congress’s lack of response, she eventually formed her league.

- Tilak and Besant formed separate leagues to prevent conflicts. They acknowledged that some of their supporters had reservations about each other. However, both leagues coordinated their efforts by focusing on their respective areas of work and collaborating whenever possible.

Tilak’s Home Rule League

- In April 1916, Tilak established the Indian Home Rule League.

- The first Home Rule League meeting organised by Tilak took place in Belgaum.

- The league’s headquarters were in Poona (now Pune).

- The scope of Tilak’s league was limited to specific regions, namely Maharashtra (excluding Bombay City), Karnataka, Central Provinces, and Berar.

- The league consisted of six branches.

- The demands of the league included Swarajya (self-rule), the creation of linguistic states, and education in the vernacular language.

Besant’s Home Rule League

- In September 1916, Annie Besant established the All-India Home Rule League.

- This Home Rule League was founded in Madras and had jurisdiction over the entire India, including Bombay City.

- It consisted of 200 branches spread across the country.

- Compared to Tilak’s league, Besant’s league had a looser organisational structure.

- George Arundale served as the organising secretary of the league.

- The main contributors to the league’s work were B.W. Wadia and C.P. Ramaswamy Aiyar.

Home Rule Movement Overview

The Home Rule Movement in India marked a crucial milestone in the liberation struggle. It was India’s response to the First World War. From 1916 to 1918, the movement gained momentum throughout the country.

- Prominent leaders such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Annie Besant, G.S. Khaparde, Sir S. Subramania Iyer, Joseph Baptista, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah came together. They recognised the need for a year-round national alliance.

- Their primary objective was to demand self-government or home rule for the entirety of India within the framework of the British Commonwealth.

- This alliance was to be known as the All India Home Rule League, drawing inspiration from the Irish Home Rule League.

Home Rule Movement Programmes

- The Home Rule League campaign aimed to promote the concept of self-government to the common people.

- The campaign had a broader appeal compared to previous mobilisations and attracted politically backward regions like Gujarat and Sindh.

- Various methods were employed to achieve the goal, including political education, public meetings, libraries, conferences, propaganda through media, fundraising, social work, and participation in local government activities.

- The Russian Revolution of 1917 provided additional support to the Home Rule campaign.

- Prominent leaders such as Motilal Nehru, Jawaharlal Nehru, Bhulabhai Desai, Chittaranjan Das, K.M. Munshi, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah joined the Home Rule agitation.

- Some Moderate Congressmen were disillusioned with the Congress’ inactivity, and members of Gokhale’s Servants of India Society also joined the Home Rule Movement.

- However, Anglo-Indians, most Muslims, and non-Brahmins from the South did not join as they perceived Home Rule as Hindu majority rule, particularly by the high caste.

Government’s Response Towards Home Rule Movement

The government responded to the Home Rule Movement with severe repression.

- In Madras, students were prohibited from attending political meetings.

- A case was initiated against Tilak, but the high court later rescinded it.

- Tilak was barred from entering Punjab and Delhi.

- In June 1917, Annie Besant and her associates B.P. Wadia and George Arundale were arrested, leading to nationwide protests.

- Sir S. Subramania Aiyar renounced his knighthood in a dramatic gesture of protest.

- Tilak advocated a program of passive resistance in response to the repression.

- The government’s actions only hardened the resolve of the agitators and strengthened their determination to resist.

- Montagu, the Secretary of State for India, commented on the government’s situation, using a metaphor involving Shiva and Mrs. Besant.

- Annie Besant was eventually released in September 1917.

Home Rule Movement Significance

The Home Rule League operated throughout the year, unlike the Congress Party, which had annual activities.

- The movement gained significant support from educated Indians, with approximately 40,000 members in the combined leagues by 1917.

- Many members of Congress and the Muslim League joined the Home Rule League, including prominent leaders such as Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Joseph Baptista, G.S. Khaparde, and Sir S. Subramanya Iyer.

- The movement briefly united moderates, extremists, and the Muslim League.

- The movement helped spread political awareness to more regions in the country.

- The movement’s signature achievement was the Montague Declaration of 1917:

- which recognised the inclusion of more Indians in the government and the development of self-governing institutions, ultimately leading to responsible governments in India.

- The declaration also marked a shift where the demand for home rule was no longer seen as seditious. This was the movement’s greatest significance.

Home Rule Movement Failures

The reasons for the decline were as follows:

- Lack of effective organisation within the Home Rule movement

- Communal riots occurred during 1917-18.

- The Moderates who joined the Congress after Annie Besant’s arrest were appeased by discussions of reforms outlined in Montagu’s August 1917 statement, which stated that self-government was the long-term goal of British rule in India, and by Besant’s release.

- The Extremists’ talk of passive resistance deterred the Moderates from participating in activities starting from September 1918.

- The Montagu-Chelmsford reforms, known in July 1918, further divided the nationalist ranks. Annie Besant herself had conflicting views on the use of the league following the announcement of the reforms and regarding passive resistance techniques.

- Tilak had to leave for England in September 1918 due to a libel case against Valentine Chirol, whose book blamed Tilak for the political agitation in India. With Besant unable to provide clear leadership and Tilak being away, the Home Rule Movement was left without a leader.

- Gandhi’s fresh approach to the freedom struggle began to capture the people’s imagination, and the growing momentum of the mass movement pushed the Home Rule Movement to the sidelines until it eventually faded away.

The Home Rule Movement marked a pivotal chapter in the struggle for India’s independence from British colonial rule. Led by prominent leaders such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Annie Besant, the movement aimed to achieve self-governance and empowerment for the Indian people. It played a crucial role in galvanising the Indian population, fostering national consciousness, and paving the way for India’s independence.

Last updated on July, 2025

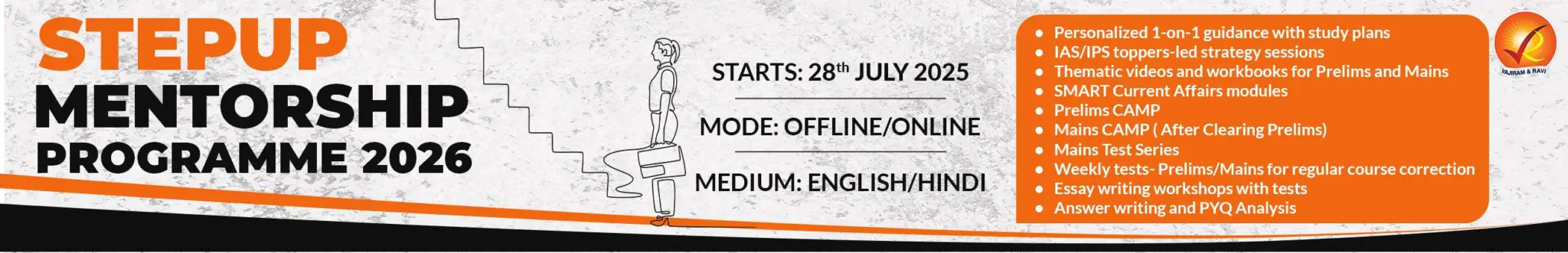

→ UPSC Notification 2025 was released on 22nd January 2025.

→ UPSC Prelims Result 2025 is out now for the CSE held on 25 May 2025.

→ UPSC Prelims Question Paper 2025 and Unofficial Prelims Answer Key 2025 are available now.

→ UPSC Calendar 2026 is released on 15th May, 2025.

→ The UPSC Vacancy 2025 were released 1129, out of which 979 were for UPSC CSE and remaining 150 are for UPSC IFoS.

→ UPSC Mains 2025 will be conducted on 22nd August 2025.

→ UPSC Prelims 2026 will be conducted on 24th May, 2026 & UPSC Mains 2026 will be conducted on 21st August 2026.

→ The UPSC Selection Process is of 3 stages-Prelims, Mains and Interview.

→ UPSC Result 2024 is released with latest UPSC Marksheet 2024. Check Now!

→ UPSC Toppers List 2024 is released now. Shakti Dubey is UPSC AIR 1 2024 Topper.

→ Also check Best IAS Coaching in Delhi

Home Rule Movement FAQs

Q1. Who changed the name All India Home Rule League to Swarajya Sabha?+

Q2. What was the main objective of the Home Rule Movement? +

Q3. Why was the Home Rule Movement started?+

Q4. In which year Home Rule League Movement was started?+

Q5. What was the significance of the Home Rule Movement?+

Tags: home rule movement quest