What is Geostrophic Wind?

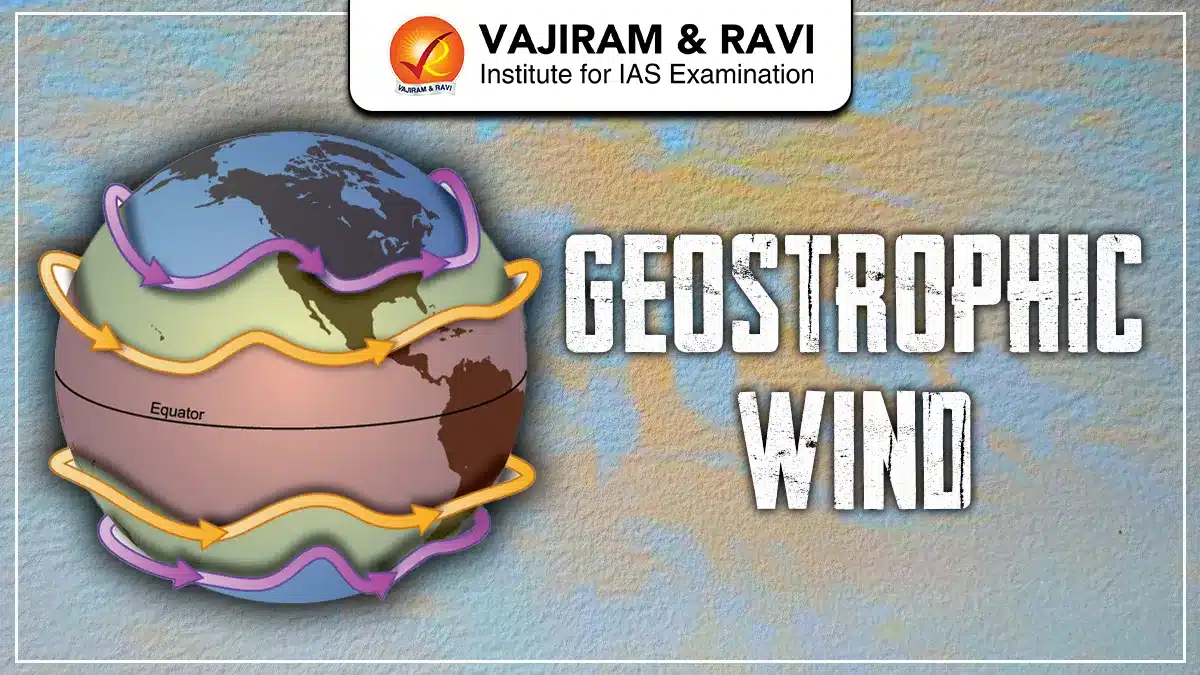

Geostrophic Wind refers to the wind that flows parallel to the isobars when the pressure gradient force is perfectly balanced by the Coriolis force. This type of wind usually occurs in the upper layers of the atmosphere, away from the influence of surface friction. As a result, the wind does not blow directly from high pressure to low pressure but moves along the isobars instead.

Geostrophic Wind Characteristics

- Flows Parallel to Isobars: Geostrophic wind moves parallel to the isobars because the pressure gradient force pulling air from high to low pressure is exactly balanced by the Coriolis force.

- Occurs in Upper Atmosphere: Found above the planetary boundary layer (generally above 1–2 km) where surface friction becomes negligible.

- Negligible Effect of Friction: Absence of friction allows the wind to maintain a steady speed and fixed direction over long distances.

- Constant Speed and Direction: Once established, geostrophic wind shows uniform velocity as long as the pressure gradient remains unchanged.

- Independent of Surface Features: Mountains, forests, oceans, and landforms do not influence geostrophic winds due to their high-altitude occurrence.

- Strongest in Mid-Latitudes: Well developed between 30°–60° latitudes where the Coriolis force is sufficiently strong.

- Wind Speed Depends on Pressure Gradient: Closer spacing of isobars indicates a steeper pressure gradient and results in higher wind speeds.

- Direction Controlled by Coriolis Force: Wind is deflected to the right in the Northern Hemisphere and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere.

- Absent at the Equator: Geostrophic wind does not exist at the equator because the Coriolis force is zero.

- Large-Scale Wind System: It develops over extensive horizontal distances and is associated with synoptic-scale weather systems.

- Theoretical and Ideal Wind Concept: Used as a reference model to understand real winds such as gradient winds and jet streams.

[my_image src="https://vajiramandravi.com/current-affairs/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/geostrophic-wind.webp" size="full" align="center" width="auto" height="274px" alt="geostrophic-wind" title="geostrophic-wind"]

Read About: Coriolis Force and Coriolis Effect

Seasonal Winds

Seasonal Winds are large-scale winds that reverse their direction with the change of seasons due to differential heating of land and sea. Their movement is closely linked to the seasonal shift of pressure belts and the apparent migration of the Sun.

- Cause and Formation: Seasonal winds develop due to unequal heating and cooling of land and oceans, which creates seasonal pressure differences and drives wind reversal.

- Role of Pressure Belts and ITCZ: The north–south movement of pressure belts and the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) with the Sun controls the direction and intensity of seasonal winds.

- Monsoon as Best Example: The monsoon system represents the most prominent seasonal wind pattern, bringing heavy rainfall during summer and dry conditions during winter.

- Impact on Climate: Seasonal winds regulate rainfall distribution, temperature conditions, agricultural cycles, and water availability over large regions.

- Upper-Air Influence: Upper atmospheric geostrophic winds help organize and strengthen seasonal wind circulation by shaping large-scale pressure systems.

Local winds

Local winds are small-scale winds that develop over limited areas due to local differences in temperature and pressure. They are short-lived and strongly influenced by surface features such as landforms, vegetation, and water bodies

- Cause and Nature: Local winds originate from localized heating and cooling of the Earth’s surface, creating small pressure gradients that drive air movement.

- Limited Extent: These winds affect confined regions and usually operate for a few hours to a day, depending on local conditions.

- Strong Frictional Influence: Local winds blow near the surface and are greatly affected by friction, unlike upper-air geostrophic winds.

- Examples: Land and sea breezes, mountain and valley winds, loo, chinook, and foehn are common examples of local winds.

Factors Affecting Geostrophic Wind

- Pressure Gradient Force (PGF): Wind speed is directly proportional to the pressure gradient; closer isobars produce stronger geostrophic winds.

- Coriolis Force: Determines wind direction and balances PGF; stronger Coriolis force results in stable flow parallel to isobars.

- Latitude: Geostrophic wind increases with latitude; absent at the equator where Coriolis force is zero.

- Earth’s Rotation: Essential for the existence of Coriolis force and hence geostrophic wind formation.

- Altitude (Friction): Forms only above the friction layer (upper troposphere) where frictional effects are negligible.

- Air Density: Lower air density at higher altitudes allows higher wind speeds for the same pressure gradient.

- Isobar Pattern: Straight, parallel isobars favor true geostrophic flow; curved isobars lead to gradient winds.

- Temperature Gradient: Horizontal temperature differences strengthen upper-air pressure gradients, increasing wind speed.

Geostrophic Wind FAQs

Q1: What is geostrophic wind?

Ans: Geostrophic wind is the ideal wind that blows in the upper atmosphere when the pressure gradient force is exactly balanced by the Coriolis force, causing the wind to flow parallel to the isobars.

Q2: At what height does geostrophic wind occur?

Ans: Geostrophic wind generally occurs above 2–3 km from the Earth’s surface where the effect of friction becomes negligible.

Q3: Why does geostrophic wind blow parallel to isobars?

Ans: Because the pressure gradient force and Coriolis force balance each other, there is no net force acting on the air parcel, so it moves parallel to the isobars.

Q4: Does geostrophic wind exist at the equator?

Ans: No, geostrophic wind does not exist at the equator because the Coriolis force is zero there.

Q5: Why are geostrophic winds important?

Ans: They help explain upper-air circulation, jet streams, weather system movement, and the general circulation of the atmosphere.